AI is not the architect: tools don’t dream, people do

Reframing the AI debate around context, consciousness and control

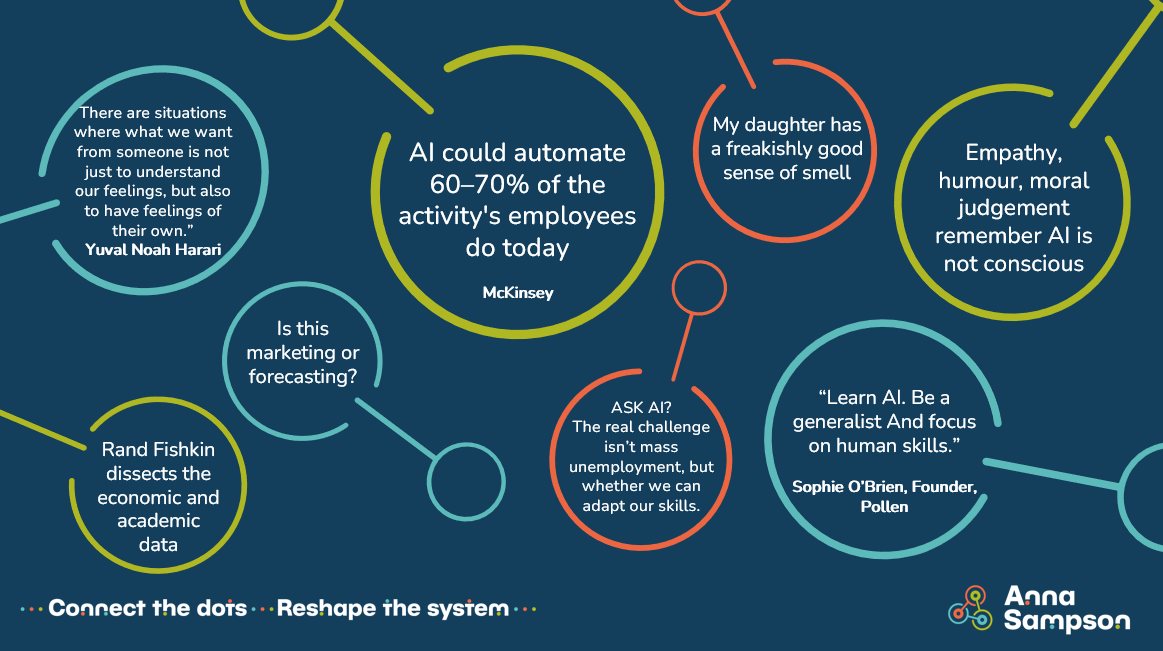

My daughter has a freakishly good sense of smell. She can identify spices by name from the other side of the kitchen. I half-joke she’s destined to be a sommelier. (Possibly influenced by my love of wine.) But joking aside - it’s one of those jobs I don’t think AI will be stealing any time soon. Why? Because it relies on a delicate mix of perception, intuition, storytelling and - crucially - human connection. AI doesn’t have a nose, and more importantly, it doesn’t have the right kind of vibe.

Sophie O’Brien, founder of Pollen Careers - a brilliant community platform breaking down barriers to entry-level work - told me recently that when she talks to young people about preparing for the future, she gives them three bits of advice:

“Learn AI. Be a generalist (because we don’t know what jobs will exist in the future). And focus on human skills.”

This stuck with me. Especially in a climate where redundancies feel like a weekly headline and the question “Will AI take my job?” is starting to feel like a nervous tick.

Fear of replacement isn’t new - it spikes every time the ground shifts beneath us. AI is simply the latest trigger. And it’s no wonder. The architecture of work - its very structure and scaffolding - is shifting beneath our feet.”

McKinsey reckons generative AI could automate 60–70% of the activities employees do today. It’s this kind of stat that strikes fear even amongst those who feel relatively secure in their jobs.

Then there’s Sam Altman (OpenAI’s CEO) the self styled father of AI, who said:

“We expect that this technology can cause a significant change in labor markets (good and bad) in the coming years, but most jobs will change more slowly than most people think, and I have no fear that we’ll run out of things to do (even if they don’t look like “real jobs” to us today).”

Easy to say if you’re a billionaire experimenting with the labour market. If you're more focused on paying your mortgage than pondering the existential meaning of “things to do,” the tone feels... detached.

Let’s pause here: many of the more apocalyptic predictions are based on extrapolations and assumptions - not reality. As Rand Fishkin points out in this excellent piece, this is marketing, not forecasting. AI evangelists - and let’s be honest, management consultants - benefit from painting a picture of inevitable disruption. It creates urgency. Urgency sells.

But as Rand points out if you look historically, mass job loss from tech revolutions has rarely materialised. The jobs shift. They don’t vanish.

I asked ChatGPT what it thinks about job loss. Here’s what it told me:

“AI won’t take everyone’s job, but it will change almost every job - fast. The real challenge isn’t mass unemployment, but whether we can adapt our skills, systems, and sense of purpose quickly enough to keep up.”

Not bad. And it lands on the most important point: change is coming. But it’s not about losing work - it’s about reshaping it.

We’re terrible at predicting the future. In the early 2000s, who imagined smartphones would become our wallets, diaries, cameras, and main source of human connection? The future is always clearer in hindsight but we don’t have that luxury.

Instead of being so laser-focused on what AI can do, we should spend more time asking what it can’t - or perhaps more importantly, what we don’t want it to.

This distinction matters. Yes, AI can mimic human qualities - and in some contexts, that’s a good thing. It’s already being used in education and therapy to offer motivation and reassurance. Natural language capabilities make that kind of support more accessible and affordable - and that’s a huge win for society.

But how we choose to apply AI is still a human decision. If we want AI to serve us well, we need to be intentional from the start. True innovation starts long before the blueprint. It starts with the question: what are we trying to build?

This is where I think we’re going slightly wrong. We’re too busy chasing wholesale automation, when we should be focused on designing thoughtful systems - with AI as material, not master builder. The real opportunity lies in considerate integration - embedding AI into human processes, not replacing them entirely. It’s not human or AI. It’s human and AI.

Let’s not forget: we’re not just automating tasks - we’re deciding which experiences we still want delivered by people. Empathy. Humour. Moral judgement. These aren’t ‘soft skills’ - they’re deeply human capabilities: context-sensitive, culturally grounded, and socially meaningful. AI can simulate them. It can even sound convincing. But it can’t live them - because it isn’t conscious.

Yuval Noah Harari puts it beautifully in Nexus:

“There are situations where what we want from someone is not just to understand our feelings, but also to have feelings of their own.”

That distinction matters. It’s why we want therapists who’ve lived through grief. Comedians who can read a room. Leaders who can navigate grey areas with grace and gut instinct.

Humour, for example, is all about timing, tone, and context. The best comedians don’t just deliver lines - they read the energy, flip their set, and adapt in real time. Empathy, too, draws on lived experience. And AI? It’s limited by its training data and our prompts. It can’t read body language or grasp the nuances of company politics. It doesn’t get the subtext. And crucially, it doesn’t have a moral compass. The ethical boundaries are ours to set - and many worry that AI, trained on biased data, is already reflecting and amplifying the worst of us.

So yes, AI can be astonishing. And yes, it’s reshaping industries - including this one (ahem, it helped me write this). To prepare for what’s next, we need to stop worrying about being replaced - and start thinking like designers.

What kind of world do we want to build with these tools?

This came up recently when I was chatting with my old friend Mary Jeffries, Chief Analytics and Data Officer at Dentsu. Her view was spot on:

“We keep thinking about AI as a layer at the top - giving it superagency. That needs challenging. AI is the foundational layer upon which WE build.”

On a recent visit to the Wallace Collection, where I saw Grayson Perry’s work up close. It was playful, political, complex, full of human contradiction. He uses AI, yes. But it’s in service to his creativity. A tool to play with - not the starting point. Not the architect. The structure comes from him - from his worldview, his contradictions, his taste. AI is just part of the build, not the vision.”

Because here’s the truth: AI isn’t the architect. Tools don’t dream. People do.

We are all still figuring out how to work with AI. Wherever it fits in the process is up to us. We have the agency.

And If we want to stay relevant - and more than that, if we want to shape a better future - we need less panic, more perspective. Less hype, more intention. And above all, the confidence to ask better questions.

Questions that help us decide what kind of work - and what kind of world - we want to co-create.

We’re not just workers adapting to a new system - we’re the architects of the system itself.

The Toolkit for human architects

Don’t just learn AI - learn how to think about it

Double down on human skills - empathy, ethics, nuance

Expect change - but not necessarily loss. Most jobs will shift, not disappear

Question the hype - especially when there’s money behind it

Design your future with agency. Don’t wait to be disrupted. Start adapting now

Let’s start a conversation

I’m Anna Sampson, a strategic consultant and storyteller helping leaders simplify the complex to make evidence-based decisions. I work at the intersection of hard business data and deep human insight - a combination that’s becoming the defining challenge in a world shaped by AI.

I collaborate with founders and senior leaders working in B2B businesses. I offer a variety of services including narrative development and storytelling, thought leadership and ghostwriting, workshops and facilitation, research, strategic counsel for boards, and systems analysis.

If you’re navigating complexity and want a fresh, strategic perspective, let’s talk.

More about me:

Get in touch:

annasampsonconsulting@gmail.com

I cycle between the optimistic and the apocalyptic. I did read one analysis on technology, that there was a tipping point in about 2008. Before that, and going back I guess to the start of the industrial revolution, new technology created more jobs than it destroyed. So we lost Farriers and Blacksmiths and Stableboys - but we gained Mechanics and Secondhand Car Salespeople and Petrol Station Staff and fluffy-dice makers. We lost many painters and framers and canvas makers and sable paintbrush wranglers, but we gained photographers and printers and 24 hour photo stalls. However - and Kodak is a great example - in the photo space Kodak employed something like 70,000 people, including for all the physical stuff - chemicals, film, photo-paper. But when they went bankrupt the 'kodak moment' was replaced with... Instagram. Which at the time employed 18 people. If driverless cars come in (and it's likely to be driverless trucks at first, that can deliver without needing to sleep, rest or pee) how many human delivery drivers will there be? I just don't yet see what volume of jobs AI *creates* to outweigh the ones it destroys. But I'm still an advocate for it - but not in its late-stage capitalist form. It should be used to bring in Universal Basic Income and a shorter working week.

great article Anna! love the toolkit. I use AI a lot as well, but I'm also concerned about the trajectory. I really hope that at some point soon the economy (and everything else) improves and companies start using AI to grow and evolve rather than just cutting costs by replacing people.